by Fritzi Horstman

I woke up this morning feeling the full effects of visiting 3 prisons in the last 2 weeks: two maximum security prisons (Salinas Valley State Prison and CSP-Sacramento) and one level 2 prison (California Training Facility): 6 days, 4 yards, working with over 400 men. I’m exhausted, depleted, disturbed, and fulfilled.

I am so grateful to have the opportunity to work with these men — our Lost Boys. Men who have been forgotten, punished, unseen, unheard, tortured and most devastatingly, ignored. Walking and spending time with this part of my community—this part of me—I see the full consequences of our societal neglect. Men who, in order to survive, must betray themselves at all levels of their being, resorting to violence and separation to feel like they belong to something in an attempt to keep themselves “safe.” The costs are incalculable.

Each prison is different. Each one has its own energy, own vibration, own levels of fear and confusion. But what they all have in common are thousands of men who need and crave connection. This is the work we and other organizations do – we create a sense of connection.

A day of our “Trauma to Transformation” program begins when the men arrive. We greet them with signs that say “You Matter.” We shake their hands and learn their names. We get a glimpse of their charms and their concerns, their capacity to connect or not but most importantly, to welcome them and put them at ease. We begin the day checking in with each participant, giving them each an opportunity to contribute to the circle, be recognized and feel included.

Then we move on to the Compassion Trauma Circle. From the center of the circle, I speak into a microphone the first of the ten Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) questions: “If a parent or other adult in the household often or very often would swear at you, put you down or humiliate you or act in a way that made you feel that you might be physically hurt, Step Inside the Circle.”

We take more steps. Physical abuse. Physical neglect. Emotional neglect. “Did you often or very often feel that no one in your family loved you or thought you were important or special? Or your family didn’t look out for each other so close to each other or support each other? Step inside the circle.” I ask them: “What child isn’t important or special? Your parents couldn’t see you because they hadn’t been seen. They couldn’t give you the ‘serve and return’ a baby or a young boy needs because they didn’t get it themselves.”

As we go through each ACE question, I invite them to voice the effects of the abuse, neglect and adversity they’ve endured. I take the time to explain how the brain reacts when it doesn’t feel safe, when it’s stressed out, when it’s in fight or flight. How the chemicals cortisol and adrenaline flood through their body, how digestion and the prefrontal cortex (the brain’s executive function center) go offline. How the body has mobilized to deal with the threat. Then I ask, “what happens when the threat lives in the bedroom down the hall? How do you ever feel safe?”

The last question is about sexual abuse. Very few take a step. I tell them they don’t need to take it, but one in six men in the United States have been sexually abused. So we all know there’s more unexposed pain and shame in the room.

I ask them to show me how many steps they’ve taken with their fingers: 5, 9, 8, 6, 7, 7, 7, 3, 8, 9, 8, 10 and on and on. Our collective trauma, on display in a roomful of men who have been imprisoned most of their lives by their parents, their upbringing, their neighborhoods and now actual prison. I stand with them, absorbing what we’ve experienced together. Finally they have an answer to their behavior, their violence, their lack of education, their inability to thrive in a society that has ultimately forgotten them.

We continue with 10 additional ACE questions including questions about racism, extreme poverty, homelessness, being a foster child, involvement with the juvenile justice system, violence outside the home, bullying and traumatic brain injuries. The circle closes in. More steps taken. The room is heavy. I take a long pause to let them process, giving them a chance to feel the effects of what they’ve been through as a child, as a teenager, as a young man, as an adult.

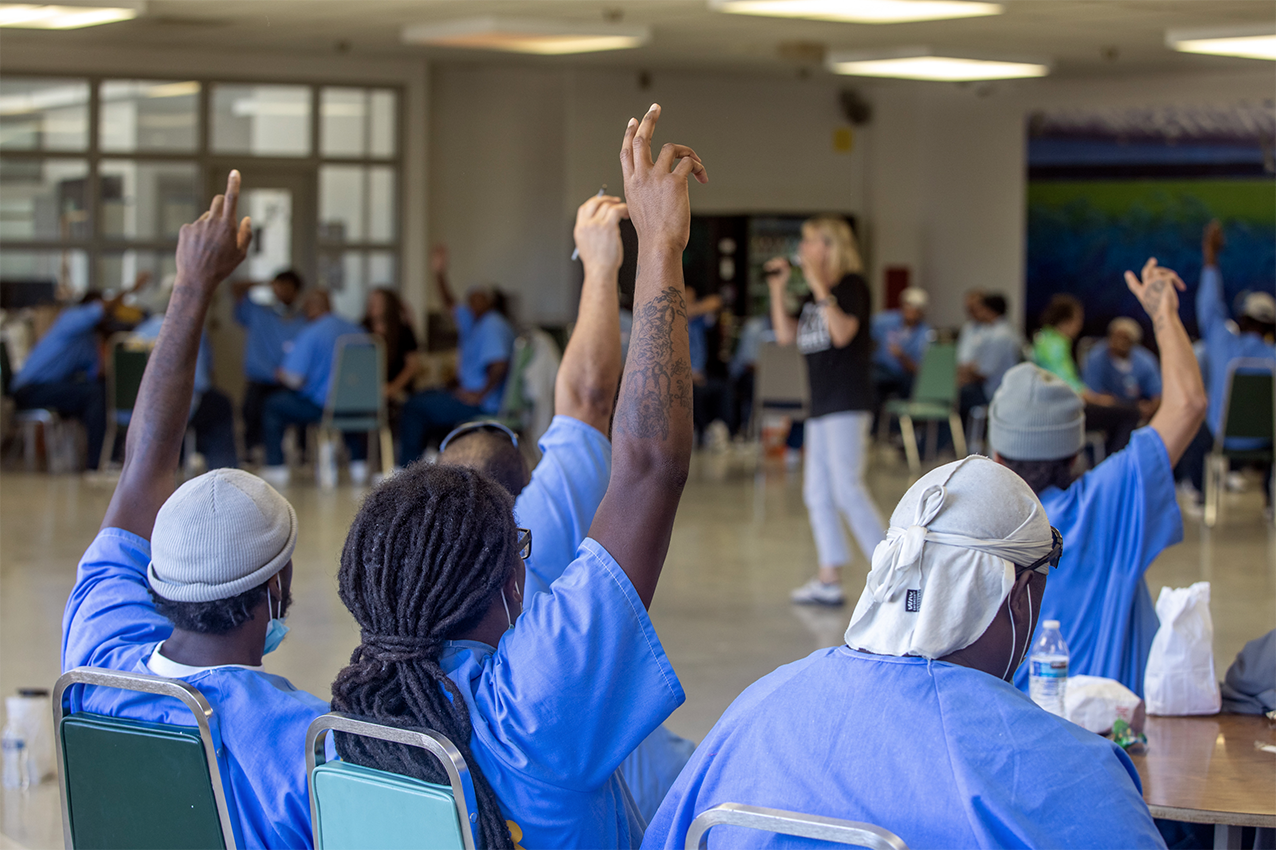

I ask them: “Has this changed how you feel about your childhood? About what happened to you?” Everyone nods. “How many of you want to learn more about trauma and how to heal?” Every hand goes up.

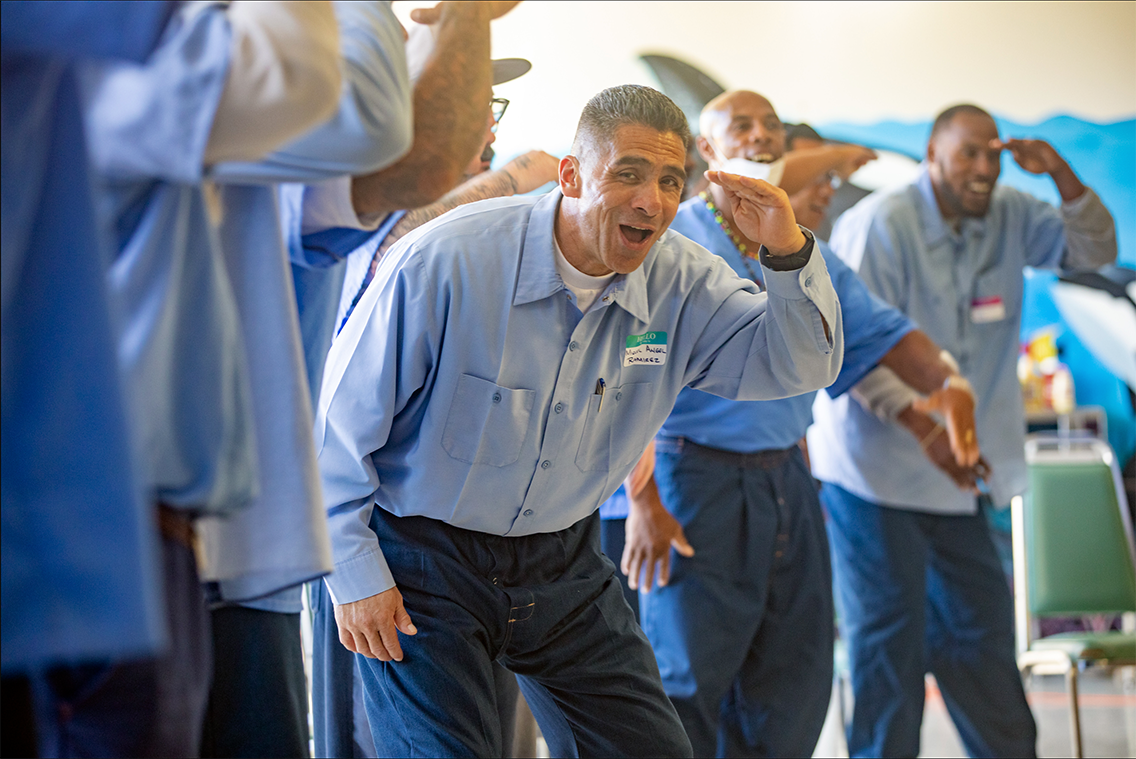

You can see it on their faces, smiling, happy, a moment of freedom. A moment of childlike wonder.

We continue the day with more exercises about addressing trauma, making connections, rewiring the brain, planting seeds of hope, possibility and transformation.

The day is over. A man comes up to me and says: “Thank you for today. I haven’t felt like this in 20 years. You don’t know what this means to me.”

As I watch them leave, their minds now returning to their realities, back to the hypervigilance and prison dynamics, I’m filled with both hope and sadness. I know they’ve been seen for their magnificence but wonder when they’ll be able to share it with each other, their communites and the world.